CAPE Acorn Award - speech to braille

Background

This project was done in the first year of my PhD as a side project, with a colleague and friend - Isabella Miele.

Deafblindness is “a combined sight and hearing loss causing difficulties with communication, access to information and mobility”[1]. This unique disability affects an estimated 394,000 people in the UK only with different degrees of severity [2]. Either or both of the disabilities that form deafblindness can be congenital or acquired in later life for example due to ageing. The combined hearing and vision loss affects significantly the life of an individual even if, when taken separately, each single sensory impairment can be relatively mild. Due to an increasing ageing population, this combined sensory disability is predicted to affect half a million of the UK population by 2030 [3]. Living with deafblindness is very challenging, both for the individual and for the family members as the combination of the two impairments creates a unique and severe disability which impacts heavily on how an individual knows and interacts with the external world. In deafblindess, not only communication is impaired but access and retrieval of information and mobility are significantly affected too. Technology for either blind or deaf people has improved significantly over the past decades. A plethora of applications and software is available to read both digital and physical documents aloud or send it to a braille keyboard. Deaf people now have the ability to speak using advanced synthesised voices, allowing for natural communication over the telephone. Unfortunately, braille keyboards can be anywhere from £1500 to £10000 [4] and if a person suffers from deafblindness most of the existing technology for either disability is no longer an option. Commercial offerings of braille displays and speech recognition software operate under closed systems, whereby devices and software obtained from one manufacturer cannot be used with those from another. It is therefore extremely difficult and expensive for a potential developer to integrate existing commercial technology for the deaf and blind, raising the barrier for the advancement and uptake of technologies to assist people affected by a combined sight and hearing loss.

Project overview

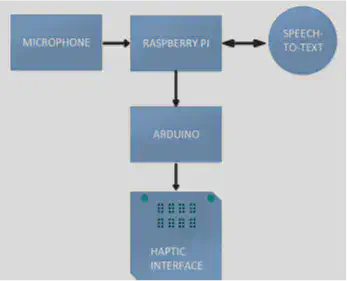

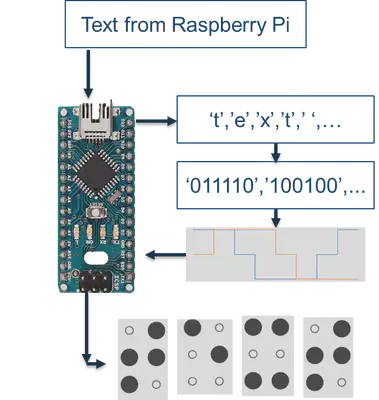

This project sets out to develop a means whereby deafblind people can communicate with the external world. In this work, we combine open source speech-recognition technologies with a haptic interface to develop a new assistive technology device which gives braille-literate deafblind people the ability to understand spoken words. Recently, it has become cost-effective and easy to interface software with custom-purpose hardware, such as in the open-source Arduino and Raspberry Pi projects. We decided to leverage this and focus on the novel aspects of our technology rather than spending development time on low-level hardware control, or on advanced machine learning algorithms underpinning a speech-recognition software. A simplified block diagram of the system developed is displayed below. Software able to convert speech directly into braille has been created using already available speech-to-text interpreters such as Sphynx and Google’s speech API [7]. Spoken words, captured by means of microphone are firstly translated to text by the speech-recognition software on a Raspberry Pi. The text is then sent serially to an Arduino which processes it into a form that can be taken by our novel haptic interface, based on miniaturized linear actuators, and finally displayed into braille.

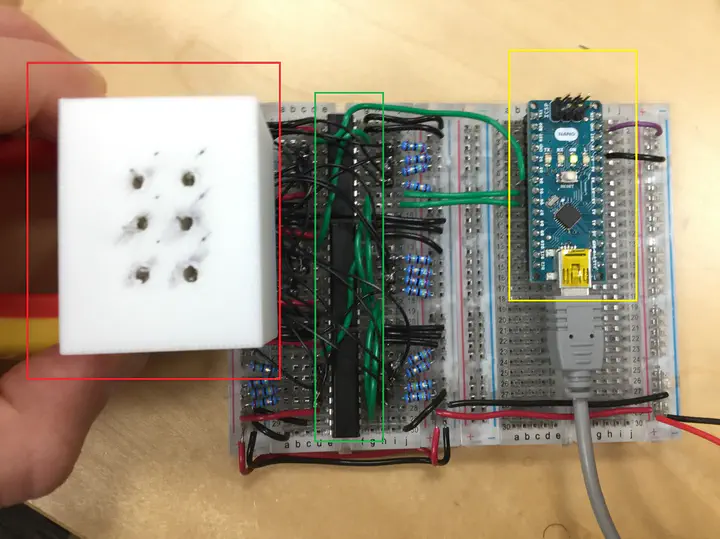

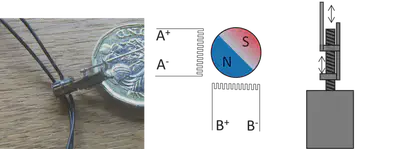

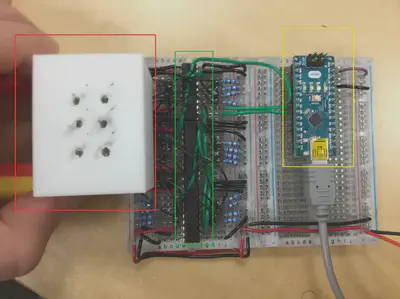

Due to the constraints of the braille letter size, a very small motor was needed to drive the mechanism. We chose a cheaply and readily available 4-wire-2-phase stepper motor (shown in figure 2) to drive the mechanism. At under 3.5mm in diameter, these stepper motors rotated in 1/8th turns at a minimum of 5ms per step (up to 25 rotations per second) allowing for ample speed and control in a very compact space. As can be seen in figure 2, the motors are extremely small with the shaft having helical grooves that were found to match up to a M1 nut. A small metal rod was soldered onto the nut to act as the pin, and another piece of metal was shaped to confine the movement of the pin along the axis of the shaft. Each of the motor’s coils were 23 ohms and required a current of approximately 50mA to provide unobstructed rotation of the shaft. In this project we used the Arduino as the microcontroller to turn the text from a computer into the actuation of pins to form the braille characters. A Raspberry Pi was used as a desktop, though the basic software will work with any computer capable of running python 3.0+. The Arduino was connected to the shift register through three pins, and code written to allow the translation of text into a number of braille characters – the system is set up so that the shift registers which control each character can ‘daisy-chain’ together to form a final braille keyboard with any number of braille characters.

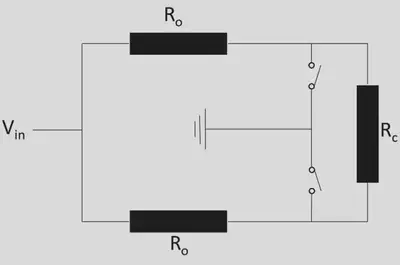

Each stepper motor required more than 40mA per coil to be driven reliably, with both coils needing to be powered at specific times in the sequence. Since most shift registers have current limits of around 20mA per pin, we opted for a heavy duty TPIC6B595N shift register that can withstand an incredible 0.5A per pin. The down side of this shift register is that the pins cannot supply current, but only allow selective access to ground. Since the motors are connected directly to the coils a method of powering them was found by using a resistor in series with the coils as shown below. The current through the coil can be found by considering Ohms law and Kirchhoff’s current law: I_c= (R_o V_in)/(〖2R〗_o+R_c )(R_o+R_c ) By taking the derivative with respect to Ro and equating to zero, the current through the coil can be maximized: (dI_c)/dR_o =0 Which results in the peak current at a resistance of: R_o=(R_c√2)/2≈17Ω This gave a ballpark estimate of what Ro should be. 20 ohm resistors were found to be adequate to allow the motors to be driven.

Software

There were two complementary sides to software developments: the microcontroller firmware that received the serial communication from the Raspberry Pi and the Python software the sent the data to the Raspberry Pi. The speech recognition software used a python module, which allowed the use of multiple speech interpreters; Google’s Speech API and Sphinx’s API were the choice in the development process due to the ease of use and highly developed recognition.

The software was set up such that it would preferentially use Google’s superior interpreter when internet access allowed for it and if not it would resort to the Sphinx interpreter. This part of the software creates a simple string of text which corresponds to what the interpreter thinks you said. After the text was created each character was converted into an array of six binary values (1 or 0), with each component of the array corresponding to the actuation of a pin within a braille character.

Figure 4 Diagram of the text-to-braille functioning of the firmware running on the Arduino. The text is received serially by the Arduino and translated into braille. The routine takes the text, splits it up into individual letters, converts each letter into a set of 6 0s and 1s that represent each pin state in a braille character. The braille character is then transduced into the necessary waveform to form the tactile character using the linear actuators.

Once this array was sent to the microcontroller it was processed into the corresponding waveforms required to drive the stepper motors and form the braille character in real life. The use of shift registers complicated this step, with the sequential transfer of bytes of information slowing the actuation of motors. In order not to draw too much current from the Arduino, the actuators were powered one after the other. This issue, however, has been rectified by adding an external battery power supply.

Discussion

The speech recognition capabilities of our project are only as good as the interpreters used, Sphynx and Google’s speech API. The better of the two, Google, is not free to use for extended lengths of time and so is not in the spirit of the project. Sphynx, on the other hand, is open source and free to use, but has poorer speech recognition capabilities. Sphynx can however be trained to improve its recognition, so it could be made more reliable for close friends and families of the deaf-blind person. The original idea for the braille character pins was to have self contained 2.5x2.5mm linear actuators so that they will fit neatly into the braille pin array. Using this technology it would also be possible to create a novel haptic interface capable of displaying grayscale images (with the scale being represented by the height of the pin). Using the mechanism shown earlier in the report the parts required would have been too costly for this project, with an estimated cost of £500-£1000 per character. Whilst the original concept was not realised, a slightly larger character at 3.5x3.5mm per pin was created at a cost of under £1 in parts. It is noted that by stacking these pins vertical space can be sacrificed to achieve the correct dimensions. It is hoped that as micromotor technology is more widely used and miniaturised that the originally planned self-contained pins could be mass produced cheaply.

Our final prototype character is capable of varying height actuation, and due to the nut-and-bolt linear actuation the pins will not move unless the motor is powered. This has an advantage over piezoelectric materials which require a constant voltage to maintain their deformation, and is akin to the E-ink displays that use very little power when not in use. Only ~55% of the motors ordered actually worked well enough to us, with many having broken connections, poor quality soldering and bent shafts. The motor were sorted by checking the connections and ability for shaft to roatate, only these functioning motors were chosen for prototyping. Testing the character’s lifespan was not possible in the timespan of the project, though the first pin created was left running for two weeks with no visible deterioration or change in electrical characteristics. All the software used in the project, apart from the speech interpreter from Google, is open source and freely accessible to everyone.

References

[1] Department of Health, “Care and support for deafblind children and adults policy guidance,” tech. rep., UK Department of Health, Mental Health and Divisional Intelligence Unit, 2014.

[2] Deafblind UK http://deafblind.org.uk/about-us/who-we-serve/, 2017.

[3] Sense https://www.sense.org.uk/.

[4] RNIB, “Supporting people with sight loss,” http://www.rnib.org.uk/information-everyday-living-using-technology-beginners-guides/beginners-guide-assistive-technology, 2017. [5] Forbes, “Breakthrough braille smartphones for the blind,”http://www.forbes.com/sites/karstenstrauss/2013/04/24/breakthrough-braille-smartphones-for-the-blind/653ba1d77f52, 2013.

[6] Kriyate, “About us,” http://www.kriyate.com/, 2015.

[7] Jasper, “Jasper project,” http://jasperproject.github.io/about.

[8] National Centre of Deaf-Blindess, “Overview on deaf-blindness,” https://nationaldb.org/library/page/1934. http://www.deafblinduk.org.uk/

[9]Development of an open technology sensor suite for assisted living: a student-led research project. James D. Manton, Josephine A. E. Hughes, Oliver Bonner, Omar A. Amjad, Philip Mair, Isabella Miele, Tiesheng Wang, Vitaly Levdik, Richard D. Hall, Géraldine Baekelandt, Fernando da Cruz Vasconcellos, Oliver Hadeler, Tanya Hutter, Clemens F. Kaminskis